Agent Tesla Analysis [Part 2: Deobfuscation]

Introduction

In the previous post we successfully unpacked Agent Tesla. We left off on a bit of a cliffhanger though, because after opening it in dnSpy it was apparent that it had control flow flattening applied. At first glance it doesn’t look too unreadable:

But if we continue looking around other functions, we can see it gets ridiculous. Take a look at this one zg5QIGkJ for example:

This took me 20 seconds to scroll from the top of the function to the bottom because it contains a whopping 800 lines of code!

How many lines of code do you think the function had originally before the flattening was applied? I’ll give you a little sneak peak of what our finished product will look like:

That’s right, only 200 lines of code. The flattening made the code roughly 4x larger than it was before and more or less completely eliminated any readbility. Unless you want to spend 500 years debugging such vomit, we’re going need to find a way to deobfuscate this.

Failed de4dot attempt

First, let’s try throwing Agent Tesla into de4dot and see if it removes the control flow like it did for the assemblies mentioned in the first post.

As shown above, de4dot as it comes by default is completely powerless against this perform of control flow flattening. No changes were made at all to the code. That means one thing: we are going to have to write something ourselves.

Analyzing the flattening

We first need to analyze the flattening to find a consistent pattern to detect. In order to do that, we will need to look at a control flow graph of the IL code blocks directly. We will use my preferred tool IDA Pro to look at the control flow graph. There is a dnSpy plugin for generating a control flow graph, but I personally prefer how IDA’s graph looks. We’re going to start by navigating to the main function 8YpydOv4 in IDA.

Let’s break down what is happening here. In the first block, the integer 0 is pushed onto the stack and then stored in the local variable index 0. Then, we have an unconditional jump to block loc_FF which then begins a series of checks on the dispatcher variable. When a check passes successfully, it executes the original code and then controls the flow by setting the variable to the next block to be executed. The number 5 here is the last check that is executed. We will refer to this final check as the loop condition because if this check fails, then it returns to the beginning of the loop. Otherwise, the function ends. It’s also worth noting that case 0 does nothing except set the next case to 1, i.e there is no actual code here being executed.

Our goal here is to connect each block to the next one in the flow, bypassing the parts that set the dispatcher variable. I feel like I should clarify the terminology I’m going to be using. When I say ‘setter’ I mean groups of instructions like this which set the dispatcher variable:

When I refer to ‘cases’ I am talking about blocks like this which check the dispatcher variable:

Lastly, before I conclude this section I think it is important to manually unflatten the function in something like notepad just so we have an idea what kind of output to expect. This was a tip that was mentioned by Georgy Kucherin in his presentation about unflattening DoubleZero (which was way more complex and is totally worth a read!) and I found it to be very helpful.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public static void 8YpydOv4()

{

ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol = SecurityProtocolType.Ssl3 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls | SecurityProtocolType.Tls11 | SecurityProtocolType.Tls12;

ServicePointManager.ServerCertificateValidationCallback = (RemoteCertificateValidationCallback)Delegate.Combine(ServicePointManager.ServerCertificateValidationCallback, new RemoteCertificateValidationCallback(5dUJkamPcT4.iwAX9d));

oBH.Z29wZduHO();

Application.Run();

}

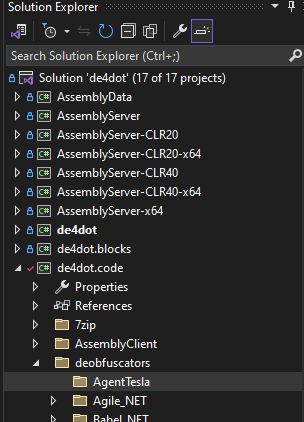

Creating the de4dot plugin

The first thing we will do is clone the de4dot repo. I am personally using this one here because it already has support for a commonly used obfuscator called ConfuserEx, but it doesn’t matter which one you decide to use.

Let’s open it in Visual Studio. The first step is to create the obfuscator by doing the following steps. First, creating a new folder in this directory:

Every deobfuscator in de4dot needs to have a DeobfuscatorInfo class. Here is what yours should look like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

/*

Copyright (C) 2011-2015 de4dot@gmail.com

This file is part of de4dot.

de4dot is free software: you can redistribute it and/or modify

it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by

the Free Software Foundation, either version 3 of the License, or

(at your option) any later version.

de4dot is distributed in the hope that it will be useful,

but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of

MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the

GNU General Public License for more details.

You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License

along with de4dot. If not, see <http://www.gnu.org/licenses/>.

*/

using System.Collections.Generic;

using de4dot.blocks.cflow;

namespace de4dot.code.deobfuscators.AgentTesla

{

public class DeobfuscatorInfo : DeobfuscatorInfoBase

{

public const string THE_NAME = "AgentTesla Obfuscator"; // Obfuscator name

public const string THE_TYPE = "agt"; // Obfuscator short name

const string DEFAULT_REGEX = @"(^<.*)|(^[a-zA-Z_<{$][a-zA-Z_0-9<>{}$.`-]*$)";

public DeobfuscatorInfo()

: base(DEFAULT_REGEX) {

}

public override string Name => THE_NAME;

public override string Type => THE_TYPE;

public override IDeobfuscator CreateDeobfuscator() =>

new Deobfuscator(new Deobfuscator.Options {

RenameResourcesInCode = false,

ValidNameRegex = validNameRegex.Get(),

});

}

public class Deobfuscator : DeobfuscatorBase

{

internal class Options : OptionsBase

{

}

public override string Type => DeobfuscatorInfo.THE_TYPE;

public override string TypeLong => DeobfuscatorInfo.THE_NAME;

public override string Name => DeobfuscatorInfo.THE_NAME;

public override IEnumerable<IBlocksDeobfuscator> BlocksDeobfuscators

{

get

{

var list = new List<IBlocksDeobfuscator>();

return list;

}

}

internal Deobfuscator(Options options)

: base(options) {

}

protected override void ScanForObfuscator() {

}

protected override int DetectInternal() {

return 0;

}

public override IEnumerable<int> GetStringDecrypterMethods() => new List<int>();

}

}

I’ll explain a bit about this class the variable THE_NAME is the name that will show up in de4dot’s console output. THE_TYPE is the short name for the deobfuscator. This one is particular important because we are going to manually specify the de4dot deobfuscator in the command line arguments to use against Agent Tesla. You can either use same values I used or your own, it’s up to you.

Regarding this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public override IEnumerable<IBlocksDeobfuscator> BlocksDeobfuscators

{

get

{

var list = new List<IBlocksDeobfuscator>();

return list;

}

}

It returns a list of IBlocksDeobfuscator’s. Each IBlocksDeobfuscator is then eventually called on the basic blocks of every function. Right now the list is empty, but we will be adding our own IBlocksDeobfuscator next.

At this point, your project structure should look like this:

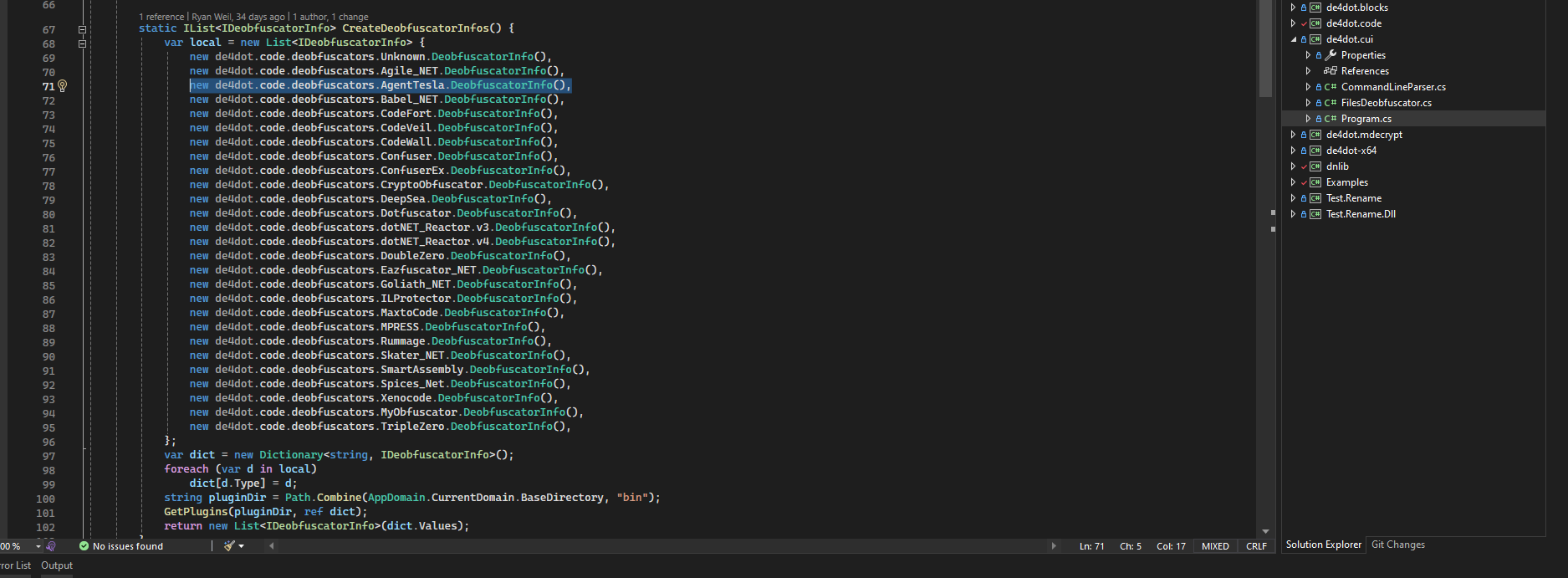

We also need to add the deobfuscator to the Program.cs file in de4dot.cui so it shows up in the actual application when it’s launched

Now, we are going to create a new class that implements the IBlocksDeobfuscator interface. I’m going to call it Unflattener.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Text;

using de4dot.blocks;

using de4dot.blocks.cflow;

using dnlib.DotNet;

using dnlib.DotNet.Emit;

namespace de4dot.code.deobfuscators.AgentTesla

{

public class Unflattener : IBlocksDeobfuscator

{

public bool ExecuteIfNotModified

{

get { return false; }

}

public Deobfuscator Deobfuscator;

public Unflattener(Deobfuscator deobfuscator)

{

Deobfuscator = deobfuscator;

}

public void DeobfuscateBegin(Blocks blocks)

{

}

public bool Deobfuscate(List<Block> methodBlocks)

{

}

}

}

This is what the default is for this class. Make sure to go back and add the class to the list in the Deobfuscator.cs file like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public override IEnumerable<IBlocksDeobfuscator> BlocksDeobfuscators

{

get

{

var list = new List<IBlocksDeobfuscator>();

list.Add(new Unflattener(this));

return list;

}

}

What we need to do is implement the Deobfuscate() method. This method is going to get called on each method in the target binary. That list that’s being passed in is all the basic blocks of the method. We want to begin deobfuscation starting with the first block of each method.

Each method begins with ldc.i4 and stloc. We can use that as a signature. However, I’m going to make new class called UnflattenerHelper to do the actual unflattening part, since I’d like to separate the logic.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

using de4dot.blocks;

using dnlib.DotNet.Emit;

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

namespace de4dot.code.deobfuscators.AgentTesla

{

public class UnflattenerHelper

{

public UnflattenerHelper(Block block)

{

}

}

}

Great. I’m going to now edit our IBlocksDeobfuscator class to call this helper class passing in the first block of the method like so:

1

2

3

4

public bool Deobfuscate(List<Block> methodBlocks)

{

UnflattenerHelper unflattenerHelper = new UnflattenerHelper(methodBlocks[0]);

}

Now, our unflattener helper should perform a check to make sure the first block matches the pattern we described earlier. This is what I came up with:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public UnflattenerHelper(Block block)

{

if (block.Instructions.Count < 2

|| block.Instructions[0].OpCode.Code != Code.Ldc_I4

|| block.Instructions[1].OpCode.Code != Code.Stloc)

return;

}

This should filter out any problematic functions.

Next, we should go and save some of the variables we described in our plan. In de4dot, the Fallthrough member of a Block corresponds to either an unconditional jump or the false condition of an if statement. The Targets member corresponds to the true condition of an if statement. Finally, the Sources list contains any block that jumps to the block.

Using this knowledge, we will save the value of the first case that gets executed as well as create a global for the current block (start block). Finally, we will store the loop condition. To do this, we will first get the fallthrough block of the start block. We will then extract the second item in the sources list since the first item will be the start block. I’ve added some checks to ensure that the start block exists in addition to making sure it has the expected count of sources.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

private Block _startBlock;

private Block _loopCondition;

private int _initialCase;

public UnflattenerHelper(Block block)

{

if (block.Instructions.Count < 2

|| block.Instructions[0].OpCode.Code != Code.Ldc_I4

|| block.Instructions[1].OpCode.Code != Code.Stloc)

return;

_initialCase = (int)block.Instructions[0].Operand;

_startBlock = block;

if (_startBlock.FallThrough == null

|| _startBlock.FallThrough.Sources == null

|| _startBlock.FallThrough.Sources.Count < 2)

return;

_loopCondition = _startBlock.FallThrough.Sources[1];

}

Now that we’ve done all this, it’s time to explore the control flow graph and gather all the cases and setters. I will create a function ExploreControlFlow() which will iterate the entire control flow graph by checking each block’s Fallthrough and Target members and recursing through them.

Something very important here is the fact that I am keeping track of the visited blocks. Why? Well what happens if the method we are analyzing contains a loop? If we don’t filter blocks we’ve visited before, our code will enter an infinite recursion when we’re exploring the blocks and ultimately cause a stack overflow.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

HashSet<Block> visitedBlocks = new HashSet<Block>();

void ExploreControlFlow(Block block)

{

if (visitedBlocks.Contains(block))

return;

visitedBlocks.Add(block);

if (block.FallThrough != null)

{

ExploreControlFlow(block.FallThrough);

}

if (block.Targets != null)

{

foreach (Block targetBlock in block.Targets)

ExploreControlFlow(targetBlock);

}

}

So now we have our code to explore the control flow. Next, we need to actually gather the relevant data. If you remember from earlier, we want to store all setters and cases. I’ve created two functions to check for either one.

IsCaseStartBlock will check if the block is the beginning of a case by looking for the four instructions which load the local dispatcher variable and compare it against a hardcoded value, branching if they are not equal. If it does not match, it returns -1. Otherwise it returns the extracted case number

IsCaseEndBlock will check if the block is the end of a case, i.e the part that sets the next case by modifying the local dispatcher variable. We look for only two instructions this time, the loading and storing of the next state to the dispatcher. Notice how in both this function and the previous one that I am making sure the operand is the same as the start block’s. The reason for this is to avoid any false positives by ensuring the local variable that is getting modified is the dispatcher variable from the original block. If it does not match, it returns -1. Otherwise it returns the extracted case number

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

int IsCaseEndBlock(Block block)

{

for (int i = 0; i < block.Instructions.Count; i++)

{

if (block.Instructions[i].OpCode.Code == Code.Ldc_I4

&& block.Instructions[i + 1].OpCode.Code == Code.Stloc

&& block.Instructions[i + 1].Operand == _startBlock.Instructions[1].Operand)

{

return (int)block.Instructions[i].Operand;

}

}

return -1;

}

int IsCaseStartBlock(Block block)

{

for (int i = 0; i + 3 <= block.Instructions.Count; i++)

{

if (block.Instructions[i].OpCode.Code == Code.Ldloc

&& block.Instructions[i].Operand == _startBlock.Instructions[1].Operand

&& block.Instructions[i + 1].OpCode.Code == Code.Ldc_I4

&& block.Instructions[i + 2].OpCode.Code == Code.Ceq

&& block.Instructions[i + 3].OpCode.Code == Code.Brfalse)

{

return (int)block.Instructions[i + 1].Operand;

}

}

return -1;

}

Now, we will update our ExploreControlFlow to save all the cases and setters that we logged. To do, I’ve created two dictionaries that each store the dispatcher number and the matching case or setter block. Keep in mind that when we save the case we are NOT including the case block itself, but the block it connects/falls through to.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Dictionary<int, Block> _casesDict = new Dictionary<int, Block>();

Dictionary<int, Block> _settersDict = new Dictionary<int, Block>();

void ExploreControlFlow(Block block)

{

if (visitedBlocks.Contains(block))

return;

visitedBlocks.Add(block);

int StartBlockNum = IsCaseStartBlock(block);

if (StartBlockNum != -1)

{

if(!_casesDict.ContainsKey(StartBlockNum))

_casesDict.Add(StartBlockNum, block.FallThrough);

}

int nextCase = IsCaseEndBlock(block);

if (nextCase != -1)

{

if (!_settersDict.ContainsKey(nextCase))

_settersDict.Add(nextCase, block);

}

if (block.FallThrough != null)

{

ExploreControlFlow(block.FallThrough);

}

if (block.Targets != null)

{

foreach (Block targetBlock in block.Targets)

ExploreControlFlow(targetBlock);

}

}

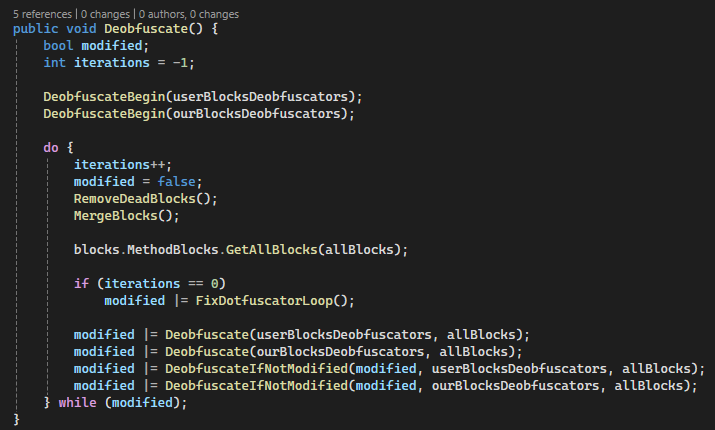

After we’ve extracted all the data we need, it’s time to perform the unflattening procedure. We will make a function called Unflatten which returns a boolean. The reason it will return a boolean is because the way de4dot works is that it will continuously call the Deobfuscate function in the IBlocksDeobfuscator class we defined until it returns false. Why? Well, de4dot has built-in optimizers which will remove dead code amongst other things. So, we return true because modifications were made. If there were no modifications made for any reason, we return false. If you want to see more, take a look at the class BlocksCflowDeobfuscator.cs:

The first thing we do is connect the starting block to the first case block with an unconditional jump (SetNewFallThrough). Then, we loop through all the setters and check if there is a corresponding case block for the setter. If so, we connect the block. I’ve also implemented a function called CleanBlock() that will remove the leftover setter instructions from the block.

When we are done unflattening, we also clean the same instructions in the start block.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

public bool Unflatten()

{

if (_casesDict.Count == 0)

return false;

Block firstCase = _casesDict[_initialCase];

_startBlock.SetNewFallThrough(firstCase);

foreach (var setter in _settersDict)

{

if (!_casesDict.ContainsKey(setter.Key))

{

Console.WriteLine("[!] Could not find next case for block in list!");

throw new Exception();

}

else

{

// Remove the code which sets the next case;

CleanBlock(setter.Value);

setter.Value.SetNewFallThrough(_casesDict[setter.Key]);

}

}

_startBlock.Instructions[0] = new Instr(OpCodes.Nop.ToInstruction());

_startBlock.Instructions[1] = new Instr(OpCodes.Nop.ToInstruction());

return true;

}

void CleanBlock(Block block)

{

for (int i = 0; i < block.Instructions.Count; i++)

{

if (block.Instructions[i].OpCode.Code == Code.Ldc_I4

&& block.Instructions[i + 1].OpCode.Code == Code.Stloc

&& block.Instructions[i + 1].Operand == _startBlock.Instructions[1].Operand)

{

block.Instructions[i] = new Instr(OpCodes.Nop.ToInstruction());

block.Instructions[i + 1] = new Instr(OpCodes.Nop.ToInstruction());

}

}

}

Now, we need to go back to our Unflattener.cs class and add the call to the Unflatten() function

1

2

3

4

5

public bool Deobfuscate(List<Block> methodBlocks)

{

UnflattenerHelper unflattenerHelper = new UnflattenerHelper(methodBlocks[0]);

return unflattenerHelper.Unflatten();

}

And that’s it. The final classes can be found here:

Deobfuscator.cs Unflattener.cs UnflattenerHelper.cs

Now it’s time for the fun part. Let’s launch de4dot with the following parameters:

de4dot <path-to-your-payload-here> -p <short-name-of-your-deobfuscator-here>

Here are some pictures of the results:

I hope you enjoyed this post. My goal in the future is to gain more experience and work on more complex obfuscation schemes. The article below shows a much more difficult type of control flow obfuscation that necessitates a different approach. I would highly recommend reading it.

Lastly, I would like to thank Ch40zz for helping me understand some logic errors that I made.